Mythic Heroes of the Texas Frontier

Well before the history of the West was written, it began circulating through the popular imagination in the form of stories, tall tales, and myths spun out of fireside banter and spreading along the frontier.

Writers from the East endured the long trek out West, where they visited saloons and penned exaggerated stories of gunslingers, outlaws, Native American wars, and life on the cattle trails. Some didn’t even bother, and wrote pulp novels about Texas without ever leaving the comfy island of Manhattan. But all Texans are familiar with the heroes of their most popular folktales. Here are a few of Texas’ best stories — true or not true.

Bigfoot Wallace

William Alexander Anderson “Bigfoot” Wallace was a native Virginian who headed to Texas to join the Texas Rangers after learning that his brother and cousin were killed in the Goliad Massacre. With the Rangers, Wallace became a veteran of the frequent battles against Mexicans and Native Americans.

The tale is that Wallace got his moniker after the footprints of the large Waco Chief Bigfoot were mistaken for Wallace’s. It’s said he once hunted down a pack of Comanche chiefs by sticking hickory chips in his shirt to protect himself from their arrows.

One legend holds that the old Texas Ranger single-handedly ran a mail route between San Antonio and El Paso. At the time, there wasn’t a man in Texas brave enough to traverse the harsh terrain along the road to El Paso, which cut straight through Apache and Comanche country. But Bigfoot wasn’t an ordinary man. Already a legend in his time — any Comanche warrior would have made his name by taking down Bigfoot — Wallace carried the mail, survived plenty of attacks, and lived to tell the tale, dying peacefully at the age of 82 in South Texas.

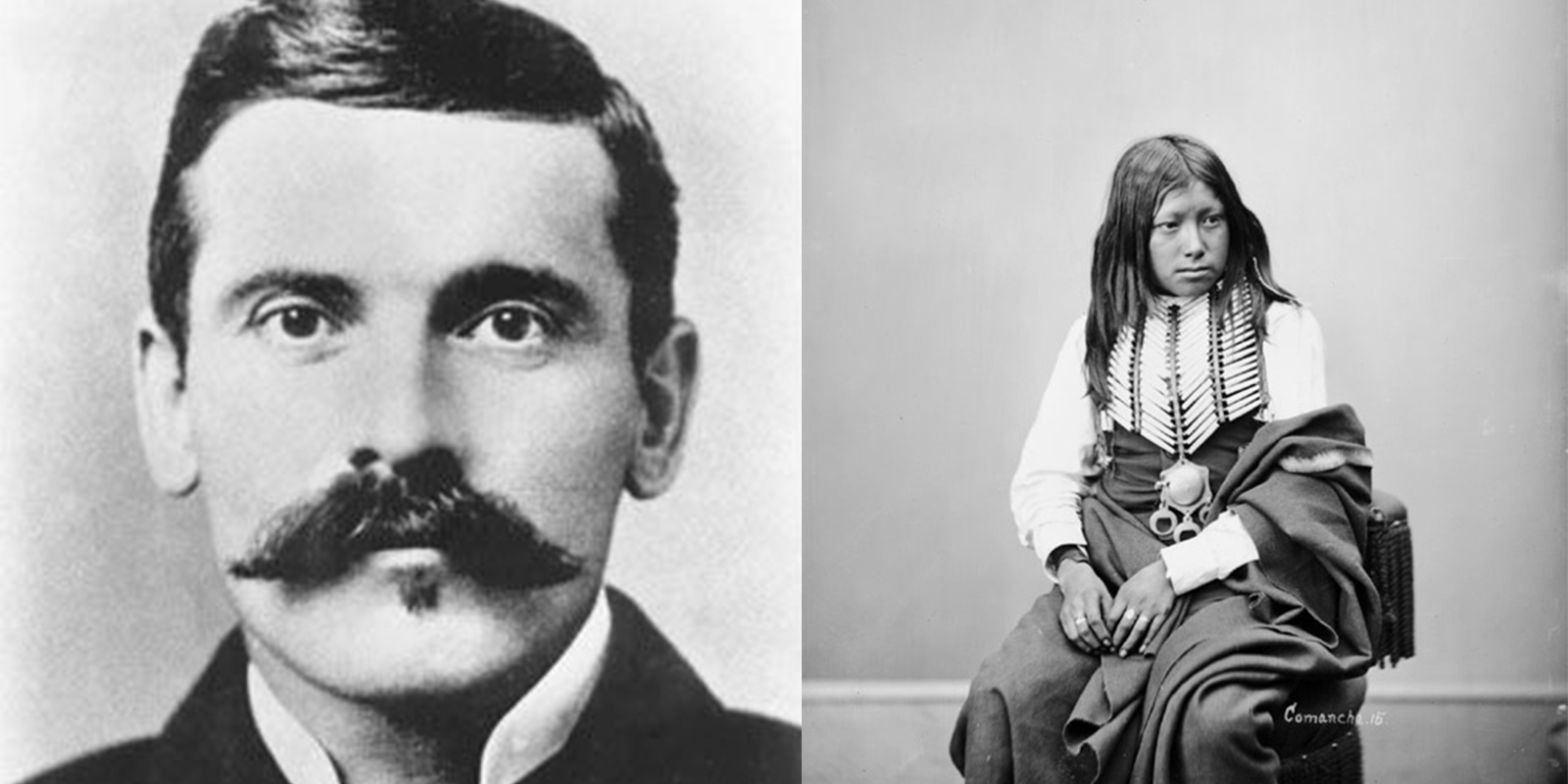

Doc Holliday

Doc Holliday may have cemented his legendary status during the shootout at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona Territory, but the famous gunslinger got his start as a gambler in the barrooms of Dallas.

Holliday was born in Georgia, where his mother raised him with impeccable Southern manners. After she died of tuberculosis, Holliday went into medicine, studying dentistry in Pennsylvania. The newly minted dentist then moved to Dallas when he was 23, not long after contracting tuberculosis himself.

Holliday’s condition (and frequent coughing) didn’t exactly endear him to his clientele. As his practice faltered, Holliday found himself spending more and more time playing cards and hanging out in Dallas’ many saloons. It was during this time that Holliday met Wyatt Earp; and when Holliday got caught up in a gunfight and was accused of murdering a man in Dallas, he followed Earp to Dodge City, Kansas, and, eventually, Tombstone. The rest, as they say, is history.

Buffalo Hump

The Comanche were the fiercest, most feared, and most skillful fighters on the Texas frontier; and for 50 years one of their most famous chiefs was Pochanaquarhip, also called Buffalo Hump. His tribe mostly lived on a wide swath of land between the Canadian River and the Llano River, sometimes camping in the Santa Anna Mountains in present-day Coleman County.

In the early days of the Texas Republic, Buffalo Hump and his tribe attempted to coexist and share the state with the new settlers. But after Texas troops killed 30 Comanche warriors, as well as five women and children, at the Council House Fight in 1840, Buffalo Hump led his warriors into the Linnville Raid of 1840 and the Battle of Plum Creek. In 1844, he met with Sam Houston and attempted to negotiate a truce by restricting Texas settlement to east of Edwards Plateau. Houston agreed, but he could not stop the flood of Texas settlers. The raids continued.

Buffalo Hump survived the Indian Wars, eventually leading the remainder of his tribe to reservations in Oklahoma. But his reputation entered the fabric of the story of the frontier. When Larry McMurtry wrote Lonesome Dove, his Comanche warrior was none other than a fictional son of Buffalo Hump.

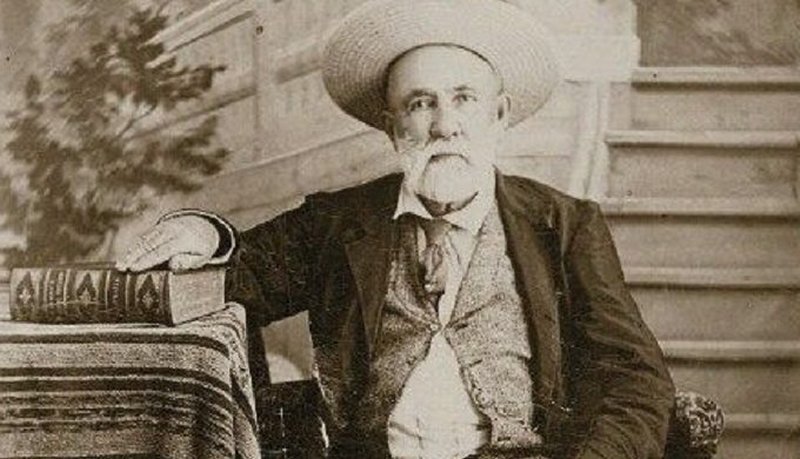

Judge Roy Bean

Before Judge Roy Bean became the famed “Law West of the Pecos,” running a combination saloon-courthouse in the tiny town of Langtry a few steps from the Rio Grande, he was a hard-living scoundrel wandering through the wide-open possibility of the West. Born in Kentucky, he left home in his 20s and landed in Mexico, though it wasn’t long before he shot a man in a barroom fight and fled to California.

Far from improving his ways, he shot another man in San Diego and killed yet another in a duel over a woman in Los Angeles. The man’s friends attempted to hang him, but the rope stretched and Bean survived, cut down from the noose by the woman he had fought for.

Texas seemed to be the only state big enough and wild enough to hold him. Bean eventually found himself installed as a notary public and justice of the peace by the Texas Rangers, who figured he was the only man tough enough to hand down the law in the sparsely populated Pecos region.

But Judge Bean became famous not for his grit, but for his wit. He once fined a dead man $40 for possessing a firearm, and then confiscated the firearm and used it as a gavel. He staged a boxing match on a tiny island in the Rio Grande when the sport was illegal in the United States. He never hanged an offender or sent anyone to prison. Instead, Bean sentenced people to help clean up or work on projects in tiny Langtry.

Judge Bean died in his saloon and courthouse in 1903. They say what killed him was the news that the state was building a power plant on the Pecos — a sign that the world was changing, and the Wild West where Judge Bean belonged was gone.

For more Texas history, explore the East Texas music highway or a few of Texas’ spookiest ghost stories.

© 2018 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance