The Ultimate Guide to Texas Wildflower Identification

The hunt for the perfect bluebonnet photo has become a Texas tradition. Every spring, drivers pull over along Texas highways so their families can submerge themselves in a field of beautiful blue wildflowers on hills, farms, and even highway shoulders. But the arrival of the iconic bluebonnet heralds the start of our wildflower season, which is about a whole lot more than just one flower.

Beyond the Bluebonnets

Texas is a utopia for wildflower lovers. Some wildflowers, like sunflowers, are common yet intrinsically beautiful. Others, like the desert-dwelling ocotillos, are rarer and more subtle in their splendor. Texas is home to a rich and vibrant diversity of wildflower species, and each region boasts its own peculiarities. Andrea DeLong-Amaya, director of horticulture at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center in Austin, says the secret lies in the size and scope of the state’s natural landscape.

“We’re blessed in Texas to have a lot of interesting plants that take advantage of different soils and geologies,” DeLong-Amaya says. Texas has vast range, from coastal to desert to subtropical to prairie to woods. “And we’re also just a big state, frankly.”

This spring, we urge you to head out in search of other beautiful flowers and plants Texas has to offer. Our guide will help you discover the best regional destinations for spotting wildflowers, introduce you to different varietals you’re likely to encounter, and maybe even inspire you to grow wildflowers right in your own yard.

Best Bluebonnet Destinations:

- St. Edward’s University, Austin, March-April: Learn more about the campus bluebonnet fields here.

- Big Bend National Park, February-March: Make a reservation here.

- Bluebonnet Festival, Burnet, April 8-10: Register here.

- Bluebonnet Trails, Ennis, April 1-30: Get info here.

- The Bluebonnet House, Fredericksburg: Drive to 413 W. Travis St. for a photo. Get info here.

The ‘Wolf Flower’: Bluebonnets’ botanical name, Lupinus, comes from the Latin word for wolf. The name “wolf flower” possibly came from early settlers’ mistaken idea that the plant “devoured” nutrients from the soil (it actually enhances the soil), or because the plant is poisonous when consumed.

Stop and Smell the Wildflowers

DeLong-Amaya nurtured a passion for wildflowers growing up in rural Michigan. Using a book about wildflower identification as their guide, she and her father would traipse through their neighborhood, explore while camping, and wander while hiking to find the species from their book. These little adventures helped her discover a love for nature.

Embarking on similar expeditions can help you and your family connect with Texas’ great outdoors. You don’t have to go far to encounter these incredible plants. DeLong-Amaya says that while you might momentarily spot wildflowers while zipping down the highway, nothing beats hiking across a nature preserve, or any natural area. Hunting for wildflowers on foot provides more opportunities for encounters and allows plenty of time to admire the intricacies of each flower.

“You might drive by some roadsides at 60 miles an hour and your attention might be caught by mealy blue sage blooming,” she says. “But if you’re on foot, you might actually stop and say, ‘Oh, little bluets,’ and look how sweet they are.”

If you’re catching the wildflower bug, read on for where to experience a spring show.

by Al Braden (1), Norman G. Flaigg (2), Joseph A. Marcus (3 and 4), and Stephanie Brundage (5)

Wildflowers Wall of Fame

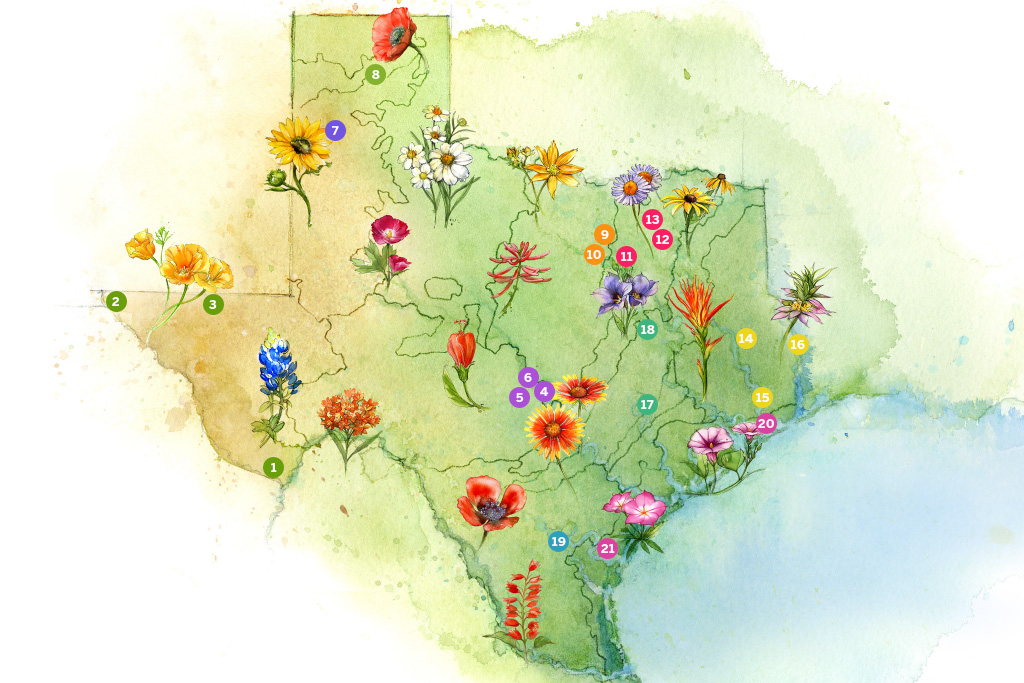

1. Big Bend Bluebonnets (West): Bluebonnets bloom across Texas, but in the far west they can grow up to 3 feet tall and transform entire stretches of desert into lush blankets of blue.

2. Ocotillos (West): Although they appear dead during dry spells, these beautiful cactus flowers bloom into life in April and May after spring rains.

3. Giant Coneflowers (East): These flowers have golden petals that fall away from a brown central cone. They look like brown- eyed Susans, only 6 or 7 feet tall.

4. Purple Coneflowers (North, Central): Lavender leaves drop away from a spiny center to make these delicate flowers look like little purple umbrellas. They are easily cultivated and can make delicious herbal tea.

5. Hardy Hibiscus (South): Also called Texas Star hibiscus, these resilient plants produce massive, bright-red flowers that can grow 3 to 4 inches in diameter.

Wildflower Facts

- Lots of choices: Texas is home to more than 5,000 wildflower species.

- Best pollinators: Attract bees with bluebonnets, Indian blanket flower, prairie coneflower, prickly pear cactus, scarlet Indian paintbrush, and white prickly poppies.

- Don’t let the bedbugs bite: Pioneers stuffed their bedding with tickseed, since it repelled bedbugs, fleas, and lice.

- Those are my nutrients: Unlike the bluebonnet myth, Indian paintbrushes are hemiparasitic and actually do steal nutrients from their neighbors through their roots.

- Lawns can be native, too: Annoy your HOA and plant the state grass of Texas, sideoats grama, for a bit of native prairieland.

10 Wildflower Regions

Some wildflowers, such as bluebonnets, can be found all over the state. However, Texas subdivides into 10 general ecological zones that are home to different wildflower species.

The Trans-Pecos (West): The spectacular wilds of the mountains’ steep slopes and desert valleys define West Texas. Look for: Big Bend bluebonnets, desert marigold, Mexican gold poppy.

1. Big Bend National Park

2. Franklin Mountains State Park

3. Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Edwards Plateau (Central): Juniper and oak woodlands, mesquite savannahs, and open grasslands spread across the Hill Country’s stony hills and canyons. Look for: butterfly weed, cedar sage, columbine, Turk’s cap.

4. Balcones Canyonlands National Wildlife Refuge

5. Enchanted Rock State Natural Area

6. Inks Lake State Park

High Plains (Panhandle): The former prairieland of the Panhandle has mostly been converted to cropland or overrun by mesquite and juniper. Look for: flowering cactus, poppy, sunflower.

7. Buffalo Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Rolling Plains (West): River tributaries cut and shape the eastern Panhandle, creating gently rolling hills and wide, flat areas. Look for: Blackfoot daisy, chocolate daisy, winecup.

8. Lake Meredith National Recreation Area, Shortgrass Prairie Ecosystem

The Cross Timbers and Prairies (North): A transitional northwestern zone is marked by plains, prairies, and some densely wooded areas. Look for: coral bean, Engelmann daisy, late boneset.

9. Bob Jones Nature Center and Preserve

10. Tandy Hills Natural Area

Blackland Prairie (Northeast): The rich, dark soil of the central land stretching between our biggest cities has primarily given over to farming and ranches, but a few preserves and parks still protect the diverse prairie life. Look for: antelope horns, bluebells, bluebonnets, fleabane.

11. Cedar Hill State Park

12. Clymer Meadow Preserve

13. Parkhill Prairie

East Texas Pineywoods (East): The rolling northeastern terrain is wooded with pine, oak, tall hardwoods, and, of course, plenty of wildflowers. Look for: bee balm, Indian paintbrush, tickseed.

14. Angelina National Forest

15. Big Thicket National Preserve 16. Sabine National Forest

Post Oak Savannah (South-Central): Oak woodlands interspersed with wide-open grasslands mark a transitional zone between the eastern forests and the western prairies and plains. Look for: blanket flowers, Indian paintbrush, brown eyed Susans.

17. Lake Somerville State Park and Trailway 18. Post Oak Preserve

South Texas Plains (South): Rolling grasslands, scrub, and brush-covered flats give way to the Rio Grande Valley’s subtropical woodlands. Look for: Engelmann daisy, red prickly poppy, scarlet sage.

19. Choke Canyon State Park

Gulf Coast Prairies and Marshes (South): Salt grass marshes, river bottomlands, and coastal prairies sprawl across the coast. Look for: beach evening primrose, Rio Grande phlox, Texas prickly pear, sea lavender.

20. Bolivar Peninsula

21. Padre Island National Seashore

Threats to Native Texas Plants

Texas’ wild areas and flora and fauna are under threat. While you can still experience the native landscape at preserves and parks, much of it has been cultivated for farm and ranch use, and the explosive growth of Texas’ large metro areas continuously threatens native plants.

“The biggest risk is habitat loss through development,” DeLong-Amaya says. “As we expand cities and build more highways, we’re taking out habitat.”

Invasive species bring further threats to Texas wildflowers. Seeds of non-native plants can stick to people’s shoes when they travel, or birds can transport seeds from other regions of the country; most frequently, however, non-native species are introduced deliberately through cultivated landscaping. When homes or businesses use non-native species in their landscaping, they can often spread into natural areas and crowd out native plants.

The simplest way to help prevent the spread of non-native plants is to avoid planting them. DeLong-Amaya says drought- resistant non-native species pose a particular problem because they can spread outside of a residential landscape and begin to take over wild places.

“It’s too bad, because sometimes people will see some of these invasive plants and say, ‘Oh, well, they’re beautiful, so what’s wrong with these? The birds might even like them,’” DeLong-Amaya says. “But we’re losing diversity because the plants that are supposed to be here are being chased out.”

Learning what plants are native to your area will help stop the spread of non-native species. Once you can identify native species and tell them apart from non-native species, you’ll be able to recognize what to avoid at the local nursery and what belongs in your yard and garden.

Illustrations by Narda Lebo.

Growing a Wildflower Wilderness

Recent years have seen a surge of interest in native landscaping, DeLong- Amaya says, in part because of concerns about water usage and drought.

“People are trying to conserve water by avoiding super water-thirsty plants,” DeLong-Amaya says. “This is both to have a smaller water bill and also for the ecological benefits of being water thrifty.”

Planting native helps preserve Texas’ native wildflowers and biodiversity. The more native plants you introduce, the more likely it is that they will spread back into the surrounding environment. And there are other benefits: Native plants are used to the soil, climate, and weather shocks common in Texas. After 2021’s severe winter storm, which saw unprecedented freezing, snow, and ice through much of the state, most native Texas plants survived and bounced back despite the unusual weather.

“A lot of non-native plants didn’t survive, and most of our native plants did just fine,” DeLong-Amaya says.

To get started growing a wildflower wilderness, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center is an excellent resource. Your local garden store will also often have passionate gardeners who are eager to share their knowledge. With a little research, planning, and care, you may not have to go on a scavenger hunt throughout the state to find your favorite Texas wildflowers — by next spring, they could be sprouting up right in your own yard.

Start a Wildflower Refuge: If you are interested in cultivating your own little native wildflower refuge, the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center is a tremendous resource. Our top five favorite resources from the center:

- Identify native plants: Find images and information about native Texan and North American wildflowers on the center’s searchable online database.

- Meet your local plants: Sign up for classes (available online, if you don’t live near Austin).

- Get gardening inspiration: Find out what’s in season.

- Talk to an expert: Ask Mr. Smarty Plants your personal questions.

- Give back to the land: Find volunteer opportunities.

Learn how to identify more Texas wildflowers here.

© 2022 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance