The Race to Preserve Texas German

In 2001, Hans Boas, a linguist at the University of Texas at Austin, was having breakfast in Fredericksburg, when he overheard a group of people speaking German at a nearby table. Boas, who grew up in Germany and specializes in the German language, was a little confused by what he heard. He didn’t recognize the dialect. He approached the table and asked where they were from. The diners — who were all in their 70s and 80s — looked astonished. What did Boas mean? They were all from right here in Texas.

Boas had stumbled upon a linguistic mystery — a unique and peculiar phenomenon known as Texas Deutsch. The speakers that morning were native Texans whose families had spoken a unique German dialect for generations, part of a long — though dying — heritage that runs rich in the central part of the state.

The encounter inspired Boas to create the Texas German Dialect Project, a scholarly effort to document and preserve this rare linguistic phenomenon. Here’s how it all began.

A Linguistic Melting Pot

There’s a simple reason why Boas didn’t recognize the form of German he overheard in Fredericksburg.

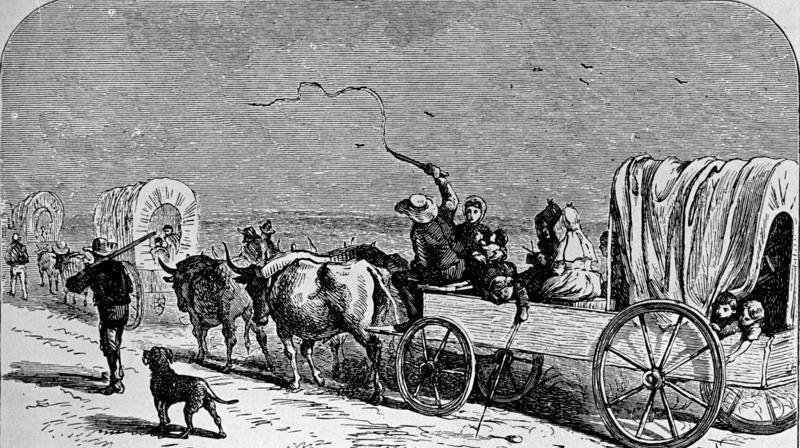

Texas’ German roots stretch back to the mid-19th century, when Germans flocked there among the area’s earliest settlers and became one of the dominant cultural groups, particularly around what is now the Hill Country. These immigrants came from many different regions of Germany, bringing with them their own distinct dialects — each with its own particular words and ways of expressing concepts and ideas.

In the new world, these varied ways of speaking mashed together into a new localized dialect, now known as Texas Deutsch.

An Evolving Time Capsule

Texas Deutsch was both a melting pot of German dialects and an evolving new form of the language. When settlers encountered things in Texas for which there were no German words, they invented new ones. Skunk, for instance, became stinkkatze — or “stink cat.”

The dialect also preserved 19th-century words and idioms that passed out of common usage back in Germany. As a result, Texas Deutsch is like a kind of time capsule of a form of German that is more than 150 years old.

The Mother Tongue

The prevalence of Texas Deutsch throughout the Hill Country speaks to the enduring heritage of German Texas.

Well into the 20th century, life in Texas’s German communities was conducted in German, from schools and churches to conversations at stores or livestock auctions. German was often the first or only language spoken at home, and English was learned as a way to communicate with people outside the tight-knit communities.

In other words, these German communities functioned in much the same way that many Latin American communities in Texas function today, with Spanish being the predominate mother tongue.

Shifting Tides

This all began to change around the time of the first and second World Wars. These two great conflicts, which pitted the U.S. against Germany, gave rise to a stigma around the use of the German language.

In 1918, in the wake of World War I, Texas passed a law requiring that all schools conduct class in English. It instilled the perception in many young German Texans that speaking German or having a German name was somehow un-American or un-Patriotic. As a result, parents began speaking more English and stopped teaching them German so as to avoid any potential stigma that might come with being Texas German.

So it was that Texas Deutsch began to fall out of use.

A Dying Language

Today, most native speakers of the dialect are in their 70s and 80s. This presents a distinctive problem for the language. As the speakers die out, the language is slowly dying with them. In a matter of 10 to 25 years, Texas Deutsch as a spoken dialect will vanish all together.

Hans Boas is doing what he can to preserve the language before it disappears. Since his first encounter with the dialect, he has met with hundreds of Texas German speakers — recording them, documenting their speech, and creating an archive that will preserve the sounds and words of the language. You can access the dialect archive on his site.

In his interviews with native speakers, Boas asks about their childhood, growing up within Texas’s German communities, and what life in the state was like at that time. Often, it is most natural for these native speakers to talk about the past in their own native tongue — Texas Deutsch.

Boas’ project, therefore, is more than a linguistic endeavor. It is its own kind of time capsule, a historical record preserving the memories and language that defined a time and place that may sound foreign but is nevertheless distinctively Texan.

Learn more about preserving our German and other Texas heritages in our regional barbecue guide.

© 2020 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance